|

In September of 2025, my work is generating the most income it ever has in my career. Yet, I'm being forced to shut down my successul operation, against my will, due to one cause alone: 95% of that revenue is being stolen by piracy and copyright infringement. I've lost more than $1 million to copyright infringement in the last 15 years, and it's finally brought an end to my professional storm chasing operation. Do not be misled by the lies of infringers, anti-copyright activists and organized piracy cartels. This page is a detailed, evidenced account of my battle I had to undertake to just barely stay in business, and eventually could not overcome. It's a problem faced by all of my colleagues and most other creators in the field. |

TRUTH: Relax! Lightning can travel no more than 20-25 miles away from a storm, in even exceptional cases. You don't need to worry about distant storms 100 miles away zapping you!

UPDATE July 2025: The World Meteorological Organization announced that an October 2017 flash stretching from Texas to Kansas was determined to be the new world-record holder for lightning flash length at 515 miles.

In 2022, a release by the WMO announced the then-record for the longest documented lightning flash, a 477-mile discharge along the Gulf Coast of the United States in 2020.

A science journal paper released in 2017 describes a lightning strike in Oklahoma on June 20, 2007 that was nearly 200 miles long, the world-record holder at that time. News articles picked up the story, raising alarm that "we'll have to rethink our lightning safety rules" because the event showed "lightning can strike farther from a storm than previously thought". These fears are unwarranted, originating from a misunderstanding of the data.

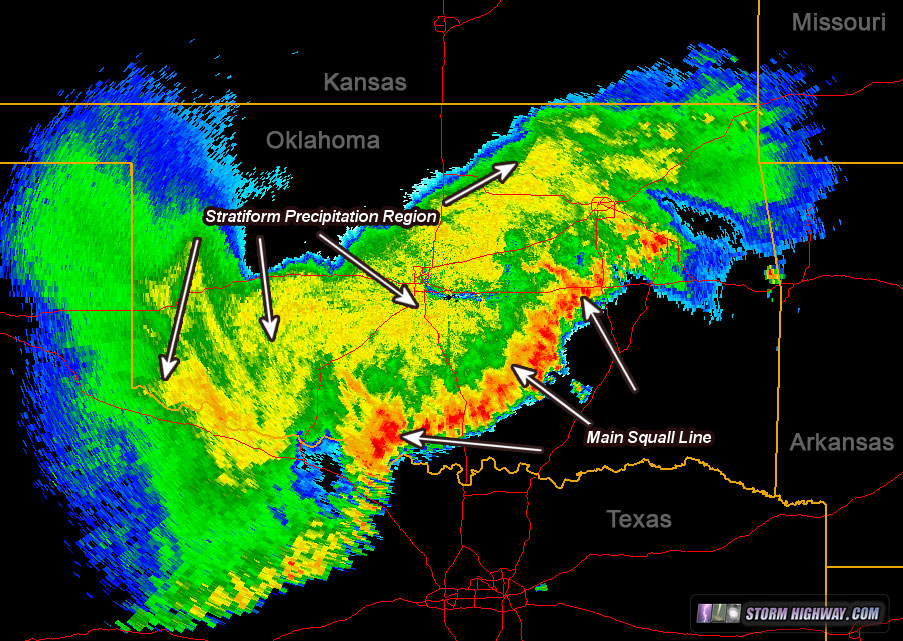

"Megaflash" lightning events are not classic "bolts from the blue" (what we call strikes leaping out into clear air away from a storm). Rather, these happen entirely within an expansive thunderstorm formation called a "trailing stratiform" region. The stratiform region is an area of electrified clouds and light precipitation that extends some distance behind the heavy leading cores of a squall line. Here is the radar image of the storm complex that produced the 2007 event:

Fig. 1: Radar image showing the convective squall line and attendant trailing stratiform precipitation region that produced the 2007 megaflash event over Oklahoma on June 20, 2007.

Thunderstorm squall lines like this are far from rare - they are commonplace in the central USA, with a couple dozen or more happening each year. They can extend for hundreds of miles, many times spanning across several states. The attendant stratiform regions of these systems are usually one contiguous mass, extending a hundred miles or more behind the leading line storms.

These stratiform shields are highly electrified, fed by the charge-generating updrafts at the leading edge of the complex. The lightning discharges that result will spread horizontally across the stratiform region, growing in a chain-reaction fashion as they tap into the vast regions of electrical charge. storm chasers call these long, horizontal lightning discharges "anvil crawlers", a colloquialism to describe the way their channels visually propagate across the sky. These "crawlers" routinely cover vast distances - lightning bolts dozens of miles long are routine events during these types of storms.

Fig. 2: An "anvil crawler" lightning discharge within a squall line's trailing stratiform shield.

As these discharges progress, they often send out periodic interconnected vertical channels that strike the ground:

Fig. 3: An "anvil crawler" lightning discharge with an interconnected cloud-to-ground component.

You've likely experienced many of these storm complexes yourself: the storm arrives with torrential downpours and frequent, loud cloud-to-ground lightning and thunder. Those are the leading cores of the squall line. As the stratiform region arrives and passes overhead, the rain tapers off to a steady light shower, while the lightning becomes less frequent with softer, longer rolls of thunder.

So, to summarize, "megaflash" lightning events are "overachieving" anvil crawler-type discharges in just such an environment, contained within a long squall line's stratiform precip area. Contrary to what some news articles say, there are no new lightning safety implications from the record event. Since the megaflash channels are entirely within a large thunderstorm complex, anyone at risk from getting struck from any part of it would already be inside the storm, experiencing lightning and thunder before and after the event.

The takeaway? The adage "when thunder roars, go indoors" still holds true. If you can hear thunder, you're within range of the next strike. There is, however, no need to worry about a storm more than 30 miles away sending a lightning bolt out to zap you. However, you should be mindful of new thunderstorms that might develop nearby or overhead, as any storm in your vicinity means the conditions might be ripe for additional storms areawide. Those storms 100 miles away also could be moving in your direction!

Bolts from the Blue

So, what about actual "bolts from the blue", the ones that reach out from storms into clear air? Those indeed are a threat if you are less than 25 miles from a storm. Most "bolts from the blue" are negatively-charged cloud-to-ground flashes that propagate horizontally from a storm for some distance, then turn toward the ground out in clear air. This is an example of one I witnessed in 2019 in southern Illinois:

Fig. 4: A typical "Bolt from the Blue" lightning flash.

How far can "bolts from the blue" strike? This photograph by Louise Denton from Australia is the longest "bolt from the blue" lightning strike I've seen documented, probably on the order of 15-20 miles away from the storm:

Flickr photo link

That example is near the upper end of horizontal distance seen for these types of events - most "bolts from the blue" travel less than a third of that range.

READ: More Weather Myths | Weather Library Home

About the Author: Dan Robinson has been a storm chaser, photographer and cameraman for 34 years. His career has involved traveling around the country covering the most extreme weather on the planet including tornadoes, hurricanes, lightning, floods and winter storms. Dan has been extensively published in newspapers, magazines, web articles and more, and has both supplied footage for and appeared in numerous television productions and newscasts. He has also been involved in the research community, providing material for published scientific journal papers on tornadoes and lightning. |

See Also:

GO: Home | Storm Chase Logs | Photography | Extreme Weather Library | Stock Footage | Blog

Featured Weather Library Article: