Storm Chasing: Frequently Asked Questions

|

In September of 2025, my work is generating the most income it ever has in my career. Yet, I'm being forced to shut down my successul operation, against my will, due to one cause alone: 95% of that revenue is being stolen by piracy and copyright infringement. I've lost more than $1 million to copyright infringement in the last 15 years, and it's finally brought an end to my professional storm chasing operation. Do not be misled by the lies of infringers, anti-copyright activists and organized piracy cartels. This page is a detailed, evidenced account of my battle I had to undertake to just barely stay in business, and eventually could not overcome. It's a problem faced by all of my colleagues and most other creators in the field. |

Storm chasing is not what most people think! Here are answers to common questions:

What is storm chasing? Who chases storms?

SHORT ANSWER SHORT ANSWER: Storm chasing is simply put, 'mobile' storm observing. It is a 'weather safari' with the intent to see and photograph natural phenomenon.

LONG ANSWER: Storm chasers are people who enjoy watching and photographing phenomena associated with severe weather. The term 'chasing' implies the careful forecasting and tracking of storms, then driving to them to make observations and take photographs and video.

Every chaser has a favorite phenomenon that interests them the most, whether it be lightning, tornadoes, hurricanes, or even cloud formations - but most chasers enjoy chasing all aspects of severe weather.

Some storm chasers are career meteorologists or storm photojournalists, but most do it for fun as a pasttime. Men and women from various occupations from all parts of the world make up the storm chasing community (see the link listed below). Many chasers take their vacation time to travel to stormy destinations for weeks and even months at a time. Some storm chasers are career meteorologists or storm photojournalists, but most do it for fun as a pasttime. Men and women from various occupations from all parts of the world make up the storm chasing community (see the link listed below). Many chasers take their vacation time to travel to stormy destinations for weeks and even months at a time. Is storm chasing dangerous? Are chasers all crazy adrenaline junkies?

SHORT ANSWER SHORT ANSWER: No, storm chasing is not dangerous. Most chasers are not 'adrenaline junkies'.

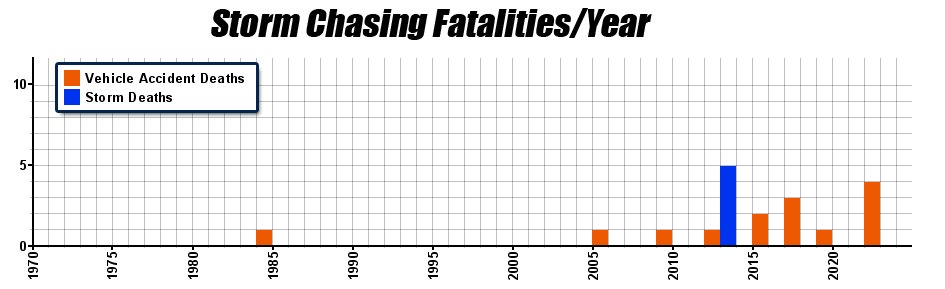

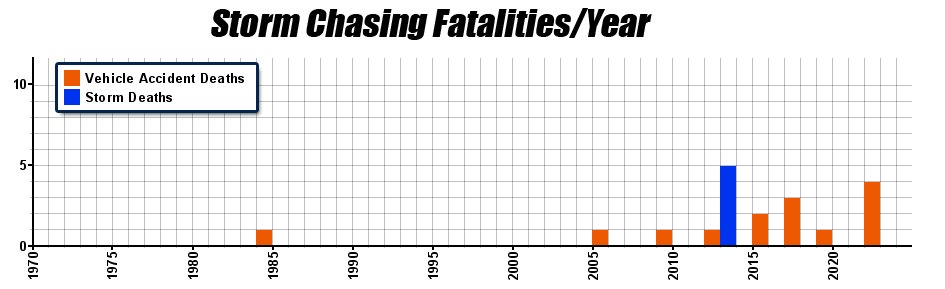

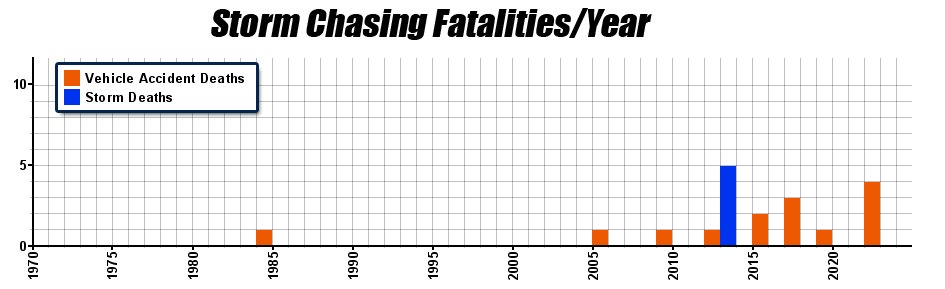

LONG ANSWER: Now that the tragic El Reno, Oklahoma EF5 tornado on May 31, 2013 has happened, this section of the FAQ obviously needed to be updated. That storm was the first to directly take the lives of chasers: Tim Samaras, Paul Samaras and Carl Young of the TWISTEX team. It was also the first to personally injure me and cause significant damage to my car and equipment, and was the closest true brush with disaster I have had at the hands of a tornado. I was only 28 seconds ahead of the TWISTEX car, on the same road - 28 seconds from suffering the same fate, I just barely escaped. I have spent countless days thinking about this, many sleepless nights since that day. So how do I feel about this question now, post-El Reno? I still don't know how to answer that exactly, but will bypass the emotional response and appeal to simple logic and reason in my attempt.

As tragic as El Reno is/was, I still don't believe that storm chasing is any more dangerous than we thought it was before El Reno happened. The statistical probability of a chaser life being lost in a tornado is still extremely small. That may be hard to see, especially while reeling in the aftermath of what happened on May 31. But the reality is that El Reno was an exceptional storm. It was a record breaker, and behaved in a way that none of us had seen before. It took many, many experienced and longtime chasers by surprise. The next El Reno-caliber storm may not happen again for many, many years. And when it does, all of us will remember May 31, 2013 and give the storm a wide berth.

But take a look at some other recreational activities: Skydiving. Whitewater rafting. Mountain climbing. Diving. Motorcycling. Many deaths happen with those activities every year, and yet they all go on. The risks are accepted because they are actually very low when all is said and done. El Reno rattled the storm chasing community, and all of us are certain to have the event always in the back of our minds now. I think for that reason, the risk of a chaser losing their life in a tornado may have actually gone down as a direct result of El Reno. With that said, I still must go with reality and assess storm chasing risks the same way I did before El Reno. Car accidents are still the more likely way a chaser will get hurt and killed. I still don't consider chasing dangerous, no more than skydiving and whitewhater rafting. And so I won't quit or scale back my chasing, just like skydivers and whitewater rafters don't despite the deaths in their field. What I will do is take the tragedy of El Reno and apply the lessons learned from it, which in my mind is the only reasonable thing to do.

With that preface, I'll continue on with my previous answer to the question "Is storm chasing dangerous? Are chasers all crazy adrenaline junkies?":

There is a widespread misconception that storm chasing is a dangerous 'extreme sport' and participants are at best fearless daredevils and at worst reckless and crazy. The truth is, however, that storm chasing is generally very safe when done responsibly. Most storm chasers are level-headed about the hobby, have no desire to put themselves in harm's way, and get tired of being typecast as high-risk adrenaline junkies. Chasing is what you might call a weather 'safari' - it's about seeing the lions in their habitat, not getting into their dens! As a longtime chaser, I would place storm chasing several degrees safer than whitewater rafting or mountain biking. If you can accept the risks of those type of activities, then you'd be more than ready for going on a storm chase expedition.

Tornadoes, for instance, are generally very easy to avoid. The vast majority of them move slowly, lumbering along in one general direction. Most are highly visible. Even the largest tornadoes are very small events in comparison to their parent thunderstorms, and consequently it's difficult to get close enough to see them. To see a tornado, a chaser has to pinpoint a small area within tens of thousands of square miles of open country - no easy task. Add to this the fact that most tornadoes don't last more than a few minutes, and you can see why simply seeing a tornado even from a distance is difficult.

Getting extremely close to a tornado is a very difficult feat. It's even less likely to happen accidentally, especially for an experienced chaser. And most important of all, it isn't necessary nor is it desired! Some of the best photography and video of a tornado is shot from one to two miles away. In fact, trying to get very close can cost a chaser some excellent photo opportunities. Once a tornado is on the ground, it may only last a minute or two, and be gone before a chaser can drive up to it. If a tornado is moving slowly and lasts long enough, a chaser might try getting closer. It can be done, the safest way being to follow behind it, though debris will often block roads. Getting extremely close to a tornado is a very difficult feat. It's even less likely to happen accidentally, especially for an experienced chaser. And most important of all, it isn't necessary nor is it desired! Some of the best photography and video of a tornado is shot from one to two miles away. In fact, trying to get very close can cost a chaser some excellent photo opportunities. Once a tornado is on the ground, it may only last a minute or two, and be gone before a chaser can drive up to it. If a tornado is moving slowly and lasts long enough, a chaser might try getting closer. It can be done, the safest way being to follow behind it, though debris will often block roads.

Ironically enough, the people in greatest danger of tornadoes and severe storms are not storm chasers, but people who do not pay attention to the weather - the person working in their shop, cooking in the kitchen, sleeping on the couch - without any radio, television or their own set of eyes to alert them of an approaching tornado. And indeed these are where many, if not the bulk, of tornado fatalities occur. In fact- if you live in Tornado Alley, the safest place to be during a severe weather outbreak is with storm chasers! By our very nature, chasers are more aware of the weather situation than anyone else, with savvy, experience and an intense focus on the storms and what they are doing. We know where to be and where not to be - a much safer situation than you would first assume.

What are the risks involved in chasing storms?

SHORT ANSWER: The main risks of chasing involve driving on the highways. The storms themselves pose a very low risk.

LONG ANSWER: While storm chasing is not the dangerous activity it is often portrayed to be, there are some risks that a chaser must be aware of and prepare for. Some of these are not what you would expect!

RELATED ARTICLE: MYTH: Tornadoes are the biggest danger when storm chasing

|

- Auto Accidents

You will hear me repeat this again and again on this site - the most dangerous part of storm chasing is not the storms - it's being on the road! In my 20 years of storm chasing, I have had more close calls related to driving than I have with storms.

Prior to May 31, 2013, there were only four known chase-in-progress deaths in the entire history of the hobby (from the early 1970s through May 31, 2013). All four of those were due to car accidents. Two of the accidents were caused by animals running onto the road at night, one by hydroplaning, and one by a drunk/impaired driver. All of these car accidents occured when the storm chaser was either on their way to a chase target or on their way home - the accidents did not occur when the driver was in 'chase mode' during severe weather. Aside from the one hydroplaning incident, weather itself was not a factor in the accidents.

The multitasking, high-distraction environment and adverse road conditions during a storm chase can further add to the basic risks of the road for a storm chaser. In the vicinity of storms, driving on roads in rain or hail can be tricky, and many rural roads in the Great Plains can become muddy quagmires when wet. Storm chasers often log hundreds of miles a day and must be well-rested to avoid fatigue. A chaser must be disciplined enough to pay full attention to the road, even when the sky is doing everything it can to divert a driver's eyes upward. Of all the dangers of chasing, driving a car personally makes me more nervous than any weather I've ever experienced - and I devote much more caution to the hazards of the road than I do to a storm. Again, photographing storms doesn't make driving risky, highway dangers are a hazard for anyone on the road, whether they are on vacation, driving to the store, or on a business trip. But as far as the risks of chasing are concerned, the chances of a vehicle accident is much greater than that of being hit by a tornado or lightning strike, or any other storm-related danger. Therefore a storm chaser's number-one safety priority must be focused on his or her vehicle and the road ahead.

Furthermore, storm chasers that drive at excessively high speeds to catch tornadoes are at a many times greater risk from an accident (not only to themselves but others on the road) than all storm-related risks combined. A classic example of this was a recent sensational news story about a close tornado intercept that described the storm chaser's supposed near-death encounter with the storm, while glossing over the fact that they had to drive 100mph on a rain-covered two-lane road to get there. This near-death experience was not the tornado - but was actually the fact that their vehicle managed to not lose control. The chances of death from the tornado could not compare with the risk from that type of driving behavior. In fact, a multi-vehicle accident involving a car traveling at that speed could easily cause more death and injury than the tornado itself.

Classifying the risk from driving Classifying the risk from driving

There is disagreement in the storm chasing community on whether to call the risk from auto accidents a 'storm chasing' risk. Some say that storm chasing, driving to work, going on vacation and a grocery store run are the same thing, in terms of the highway dangers encountered. So, it is argued that a car accident during a storm chase expedition may not be fully classifiable as a 'chasing accident'. My argument for classifying car accidents as 'chasing accidents' is that storm chasing is driving. Driving and chasing are inseperable. Not only driving, but an abnormally high amount of it. Storm chasing requires long drives to a target early in the day, long drives during the chase itself, and long drives on the way home.

Highway safety professionals have always quantified the driving risk in terms of the number of deaths per mile traveled. So, as you drive more miles, your risk increases. Because storm chasing is, in essence, near-constant driving, I argue that the increased risk from all of that extra mileage can indeed be classified as a storm chasing risk in itself. In other words, storm chasing directly exposes the participant to an abnormally higher risk of auto accidents than that of the average person. Another way I look at it is by this analogy: if a Mount Everest climber slips on a ledge on his way back down the mountain and falls to his death, do you classify it as a mountain climbing death, or one related to falling, ice, his shoes or his equipment?

Breaking down driving risks

This table shows the types of incidents that have caused fatal storm chasing car accidents:

|

| Accident Cause |

Fatalities |

| Stop sign running |

|

| Hydroplaning |

|

| Animal in road |

|

| Hit by second vehicle after stopping |

|

| Drunk driver |

|

|

To further break down this topic, here are the primary dangers to storm chasers on the road:

- Distracted Driving

Laptop or cell phone use while driving (to look at radar images) presents by far the biggest danger in storm chasing. Few other factors present such a grave risk to people on the highways than a driver operating a vehicle at high speed who isn't looking at the road. The distracted driving risk in storm chasing has primarily manifested in stop sign running incidents that occur at the intersections of rural two-lane roads. When a collision occurs between two vehicles in this type of accident, vehicle speeds are high and impact forces are violent. The data clearly shows this type of incident is responsible for the greatest number of storm chasing deaths (see the above chart).

- Hydroplaning

Many storm chasers have had hydroplaning accidents, which have caused four chaser fatalities. The 'push' to catch/keep up with a storm often tempts a storm chaser to drive faster than is safe.

Animals AnimalsTwo of the four known chase-in-progress deaths were caused by animal-on-the-road accidents at night. storm chasers log many miles late at night, a time when wildlife (particulary deer) commonly dart out into the road. Many, if not most, storm chasers have hit animals during a chase. It happened to one vehicle in our caravan in 2005. - Road ice

As 'chasing' and photographing winter storms (ice storms, blizzards, etc) becomes more popular, I expect to see more of these types of accidents. Many have already occured that to my knowledge, have thankfully not yet resulted in serious injury or death to a storm chaser.

- Excessive speed

Sudden sharp turns and other road hazards can make any of the above threats even more deadly when a storm chaser is traveling at a high rate of speed.

- Other motorists

Even the safest storm chasers are still ultimately at the mercy of the behavior of other drivers on the roads. One of the known chase-in-progress deaths was caused by a drunk driver heading the wrong way on an interstate.

- Dirt roads

While not much of a threat to one's life, dirt roads can be major hazards. In the Midwest and Plains, many secondary roads are unpaved. When these roads get wet from rain, they turn into a surface that behaves exactly like black ice to a vehicle. Even four-wheel-drive trucks can easily lose control and/or get stuck on dirt roads. Scores of vehicles are mired by these dirt roads in the Plains every spring. While getting stuck in and of itself is usually 'only' a major (and costly) inconvenience, it can put a storm chaser into a life-threatening situation if they can't get out of the path of a tornado or large hail.

- Inaccurate maps

Even modern GPS mapping software suffers from countless errors when it comes to secondary roads. It is common for an indicated paved road to be unpaved and treacherous/impassable, and for a through-road shown on the map to end prematurely or not exist at all. These mapping blunders have trapped storm chasers on numerous occasions with no escape routes, causing hail damage and close calls with tornadoes.

I lost one of my friends and chase partners in 2009 to a car accident that occured while he was on the way to a chase target. The accident was caused by a deer.

- Financial and Social Risks

Storm chasing can be a very addicting activity once one gets 'bitten by the bug' - so much so that I'm placing the financial and social risks of chasing in this list - and at that, above the threat from storm hazards! My reasoning being, it's more likely for a storm chaser to harm themselves financially and/or socially from chasing than it is for them to get hit by lightning or a tornado.

The urge to not miss a big outbreak can be a strong one. Things like media attention and the mostly-misguided idea that the participant is helping to 'save lives' can often make chasing seem more important than it actually is. Granted, this type of dedication to any hobby (golf, fishing, skydiving, sports, etc) can be similarly destructive, but storm chasing seems to present a higher-than-typical risk than other leisure pasttimes.

It's easy for any chaser to make the mistake of putting seeing storms and tornadoes above virtually anything else in life. Lost friends, broken marriages/relationships, high debt, lost income and failed careers are common in the world of storm chasing. I myself have not been immune to the temptation to give chasing a higher priority than it deserves. Seeing chasing for what it really is - just another hobby - and finding a balance between storms and other things in life is one of the most important things a storm chaser can learn. In the end, 'Nobody Cares what you've done as a storm chaser! Don't let something take over your life that in the end, doesn't mean much.

- Lightning

storm chasers spend a lot of time in the vicinity of thunderstorms. Over the years, several storm chasers have had close calls with lightning strikes. This risk can be minimized by staying in your vehicle as much as possible, especially during periods of high lightning activity.

- Large Hail

Encounters with moderate-sized hail are common when photographing storms, and most storm chasers can expect to pick up at least a few hail dents on their vehicles each season. Most storm chasers don't mind these occasional minor 'battle scars', but those with expensive vehicles might be concerned.

In rare events, a storm chaser could find themselves in hail larger than baseballs, which can do serious cosmetic damage to a vehicle as well as break the windshield and/or the windows. Any broken window may result in glass fragments that can cause minor cuts. For the most part, the worst hail can be easily avoided by the experienced chaser and therefore is not a big risk. An even lesser risk is the remote chance of a head/body strike by a large hailstone while standing outside, which could easily cause serious injury. Even small hail impacts can be painful to skin, so storm chasers should stay in their vehicle when hail is falling.

- Strong Winds, Debris and Storm Aftermath

High winds often topple trees and power lines, break branches, blow objects into the roadway. Again, this takes us back to the driving risk. These objects can make travel hazardous, particularly after dark. More than once I've come upon fallen power lines across the road, in one instance hitting a wire before I could stop. Debris on the road is not always easily spotted in time to stop your vehicle. In agricultural areas like the Great Plains, livestock can wander onto the road after a storm damages roadside fences. Several storm chasers have had close calls with cows that walked through a tornado-damaged fence onto the road. Pictured at right are cows walking on Highway 183 near Greensburg, Kansas after a tornado wiped out fences along the roadway.

In some cases, high winds can carry small debris like gravel and tree branches that can break vehicle windows. A chase vehicle in our caravan in 2001 suffered a broken rear window after wind-blown gravel shattered the glass:

- Tornadoes

You might be surprised that I've put tornadoes last on my list of storm chasing risks. After the May 31, 2013 tragedy, I thought long and hard about changing this section of the FAQ. The fact remains that the risk from tornadoes to storm chasers is still small compared to the others. The El Reno tornado on May 31, 2013 was record-breaking and highly anomalous, and while certainly tragic, is not a representative situation typical to 99.999% of tornadoes documented on chases.

Tornadoes are easy to avoid. It is actually hard to get in the path of a tornado, even on purpose. It's difficult for a storm chaser to even see a tornado at a distance on most chases, let alone get close enough that driving into it is even a remote possibility. Tornadoes are sort of like freight trains, moving along a track at a fairly constant speed and direction. If they do shift direction, it is usually in a gentle curving motion. All you have to do is stay out of the tornado's track and you'll be fine. Since tornadoes often travel at angles to roadways, the intersection of tornado paths and roads are few and far between, meaning that you have to be at exactly the right place at the right time to have a tornado strike you. Many storm chasers (including the TIV crew featured on a recent Discovery Channel series) have been making concerted efforts to make close intercepts of tornadoes for years, with very few successes. A chaser getting into a tornado accidentally is such a small risk that it is almost negligible.

Before May 31, 2013, I made the following statement here: "Now I know that eventually, a storm chaser will get seriously hurt or killed by a tornado. I think that it's inevitable. But I contend that it will be a rare exception to the rule, as it has been up to this point. Tornadoes historically have not been threats to storm chasers, at least not one worthy of anything more than a passing mention." Now that the inevitable has happened, what should I say? I still believe that the risk from tornadoes is negligible to storm chasers. El Reno will certainly go into the mental "knowledge bank" of storm chasers, but looking at the past track record of the hobby, I don't see a justification to begin lessening emphasis on the risks from driving, for example.

Was the movie "Twister" realistic?

SHORT ANSWER SHORT ANSWER: Parts of it, yes, others, no. Twister mainly failed to portray the long drives, waiting and tornado-less days that comprise 95% of chasing.

LONG ANSWER: 'Twister' is a movie about storm chasers that came out in the summer of 1996. As is with most action movies, 'Twister' is full of inaccurate science, bad stereotypes, and misrepresentations of storm chasing in general. Nonetheless, it was entertaining- and to most chasers, this was 'our' movie. Despite its flaws, 'Twister' vindicated the storm chaser. All of a sudden, chasing tornadoes was 'cool' and the world understood, to some degree, why someone would do what we do.

In fact, Twister had a profound effect on storm chasing. Even before the movie, chasing was already an increasingly popular activity. After the movie came out in 1996, thousands of people started (and many still are) chasing storms as a direct result of the film. The influx of people and interest in chasing from the movie has introduced both positive and negative factors. For example, a single supercell storm in the Plains can often be surrounded by hundreds of chasers, causing traffic and overcrowding.

There are a plethora of web sites by chasers that refute the errors in 'Twister', so I won't go into much detail - but the following Hollywood fabrications are worth a mention:

- MYTH: Chasers see lots of tornadoes every day.

REALITY: In Twister, a storm chaser's schedule for the day goes something like this: Wake up, eat breakfast, see tornado, see tornado, eat lunch, see tornado, see tornado, eat dinner, see tornado, go to sleep. The truth is, anyone who chases for the first time expecting a Twister-like experience is bound for disappointment!

In reality, most chasers will be happy if he or she sees one or two tornadoes in an entire season. For every few minutes of time witnessing a tornado, a chaser spends days on the road. In the real storm chasing world, time is divided something like this: 90% driving, 7% waiting, and about 3% of actually seeing storms. Most chasers report that they see a tornado a little less than once every fifteen days they go out to chase, and after driving thousands of miles. I chased the Great Plains (A.K.A. Tornado Alley) for four years before I saw my first tornado.

In rare instances (usually one or two events per season), chasers see many tornadoes in one day. 2004 was also a rare year in which storm systems produced multiple-tornado days for many chasers.

Storm chasers must endure a lot of hard work, discomfort, disappointment and expense in order to see tornadoes, an aspect of the hobby that Twister failed to portray.

- MYTH: Chasers want to get in the path of the tornado, or as close as possible to it.

REALITY: Storm chasers want to witness a tornado, not be part of it. Our main objective is to observe and photograph the phenomenon at a safe distance.

- MYTH: Chasers will get to a tornado at all costs: including by driving on 4wd-only roads and through private fields, etc.

REALITY: All storm chasers want to see a tornado, and will spend lots of vacation time, money, and effort to reach that goal. But chasers are not crazed high-adrenaline lunatics that will put life and property at risk to get to a tornado. Most chasers have missed tornadoes because it was not safe or considerate to continue on. For example, on May 24, 2002, I missed the brief tornado in Vernon, Texas because I felt it was unsafe to continue driving at highway speeds on the rain-slickened roads. That turned out to be the only tornado our team saw during my entire chase vacation, and I was very disappointed at losing that opportunity. But seeing the tornado was not worth putting myself or others on the road in danger.

- MYTH: People can survive being inside a tornado.

REALITY: The movie dipicted several scenes where the characters found themselves literally in the center of the tornado with little or no shelter, yet came out unscathed. Flying debris (bricks, cinderblocks, boards, cars, pipes, etc. at 100+ MPH) is always present in a tornado, and will kill or seriously maim anyone who ends up in the middle of it - whether they are tied to a water pipe or not.

- MYTH: You can sit down and eat a meal during a tornado outbreak.

REALITY: There is no time to stop and relax during a tornado outbreak-in-progress, unless you want to miss all of the action. Even making one too many bathroom stops can cost you an intercept!

Do storm chasers enjoy seeing severe weather cause destruction and harm?

SHORT ANSWER SHORT ANSWER: No!

LONG ANSWER: It is incomprehensible that anyone would wish death and destruction on others. Storm chasers certainly don't fit that description. Inadvertently, a few tornadoes and severe storms will hit houses, towns and businesses and sometimes cause injury or worse. However, the vast majority of tornadoes touch down in open country, missing structures and damaging nothing but trees and cornfields. Chasers are after the tornado itself, not the destruction it causes. Chasers cannot control when, where and what a tornado will strike. We prefer a beautiful tornado over open country, with nothing but tree limbs and dirt in its debris cloud. It's impossible to fully enjoy a tornado that causes injury or loss of property, it is a bittersweet experience that taints an otherwise perfect chase day. While admittedy a tornado destroying a structure is a phenomenal sight to witness (for anyone, not just the storm chaser), it is not one that is sought out nor enjoyed by chasers.

I'm not a racing fan, but I can draw this analogy. NASCAR is a sport enjoyed by millions. Races are attended by more than 100,000 fans and televised nationally. In auto racing, crashes, damaged cars and injury are common. No one is wishing injury or death on a driver, but it is inevitable that it will happen from time to time. Is that reason to stop racing, or for people to stop being racing fans? Should these fans be guilty for being racing fans?

Tornadoes are natural forces that we cannot control. Storm chasers are out to witness and learn about this spectacular phenomenon, and a successful intercept is a great experience. But no chaser wishes death or destruction on anyone, nor do we remotely enjoy it when it happens.

For more reading on this subject, I elaborated on this topic at greater length on my blog.

What is 'core punching'?

'Core punching' refers to driving through a storm's heaviest precipitation area to get to a better location, intentionally or unintentionally ( NOT driving into a tornado, as portrayed in 'Twister'). For instance, let's say a chaser is on the north side of a storm, and wants to get to the south side to get a better view of the developing tornado. Now there's only one road that leads in that direction, but the heavy precipitation area of the storm happens to be passing over that road - the chaser may elect to go through the precipitation (core punch) to get where he/she wants to go.

The biggest dangers associated with core punching involve your car: 1.) the reduced visibility and hazardous road conditions caused by heavy rain and high winds, and 2.) large, damaging hail (sometimes baseball to softball-sized) that can shatter windows and inflict huge dents.

Every year, many storm chasers experience costly damage to their cars from hail as a result of core punching. As a result, most experienced chasers will avoid a 'core punch' at all costs, even if it means missing a tornado.

The low visibility associated with a 'core punch' may also put a chaser at risk to drive into the path of a tornado that they cannot see.

Where do you chase storms?

SHORT ANSWER SHORT ANSWER: Storm chasing can be done virtually anywhere.

LONG ANSWER: There are storm chasers from all parts of the world, from the USA to Australia, from England to Argentina. Chasers like to observe the weather where they live, but will occasionally travel to other parts of the globe where certain phenomena is common (tornadoes in the Central Plains, lightning in Florida, hurricanes on the Atlantic coast, etc.).

Chasing can be done successfully virtually anywhere on earth. Although certain phenomena like tornadoes are less common outside of the typical 'hot spots' like the US Great Plains, thunderstorms occur worldwide and offer the casual chaser plenty of sights and photogenic scenes to capture - no matter where you may live. For instance, I lived in West Virginia for over 16 years, and had plenty of successful storm chasing outings every year. How do you become a storm chaser?

SHORT ANSWER: Just do it!

LONG ANSWER: Unless you want to become a SKYWARN spotter, there are no procedures, certifications or permits required to get involved in a weather-related hobby. Like any other pasttime, you just start doing it. You don't need any equipment other than a camera and possibly a notebook to record your observations. A NOAA weather radio is especially helpful. Access to weather data and other information on the Internet can help you learn a great deal about various aspects of the field. Of course, an automobile helps if you want to see events that occur away from home, but you can always see and photograph storms from where you live. Joining a weather-related forum like StormTrack to share questions, photos and observations is a great way to link up with other people in the storm chasing community and further your knowledge.

There's no hard and fast definition of what storm chasing is and what is not. For example, tornadoes are not the main subject of interest for many chasers. If you just want to go out and observe the weather in your community (or even in your backyard), go for it. If you're already doing that, you fit the general definition of a 'storm chaser' in its simplest sense. There's no hard and fast definition of what storm chasing is and what is not. For example, tornadoes are not the main subject of interest for many chasers. If you just want to go out and observe the weather in your community (or even in your backyard), go for it. If you're already doing that, you fit the general definition of a 'storm chaser' in its simplest sense.

It's important to use common sense, drive safely, avoid taking risks, and be considerate to others (motorists, residents) while on any chase. Curiosity seeking, sensationalism, competition and risk-taking are not what storm chasing is about, and those who practice such things are generally frowned upon by the storm chasing community.

Chasing in Tornado Alley

It's worth mentioning that it takes experience and at least a general understanding of severe weather forecasting and storm identification to successfully and safely chase tornadoes. Just like you would with whitewater rafting or rock climbing, a person new to storm chasing should always first venture out with a group of seasoned chasers to familiarize themselves with the ins and outs of the hobby.

It's not a good idea to go alone on your first chase. You'll have a hard time finding tornadoes if you simply go out on the road with no prior experience. Not only that, but you also put yourself at risk to get into potentially dangerous or damaging situations like large hail or high winds. Experienced chasers recognize these situations in advance and can take evasive measures.

How much does chasing cost?

Storm chasing is an expensive hobby, mainly because it involves a great amount of travel. Many chasers live away from the Great Plains, necessitating a long drive, flight or train ride to get to Tornado Alley.

Once on the Great Plains, chasers can drive over 500 miles on a typical chase day. Chasers can log several thousand miles per week, meaning that vehicle maintenance such as oil changes and tire care must be considered. Chasers spend nights in hotels, paying full price for rooms. Since a chaser doesn't know what city, town or even state that they will end up in from day to day, it is impossible to make advance reservations or get multiple-night discounts.

With gas and lodging, a typical week of storm chasing on the Plains can cost as much as $1500. Frugal chasers often carpool and share hotel rooms to split costs. Professional storm chasing tours cost between $2000 and $3000 for a ten-day trip, which includes all lodging and fuel costs.

What equipment do you need to chase storms?

There are no equipment requirements for chasing storms, other than a car! Gear is really up to the individual chaser to decide. Chasers have varying opinions on what type of gear to take along. Some have fully decked-out vehicles with every conceivable gadget available, while others take nothing more than a cell phone and a camera. Most chasers fall somewhere in between these two, however. You basically should take along everything you would take on a vacation - cameras, first aid kit, clothes, etc. Weather data is helpful to have on the road, which can be obtained as simply as a NOAA weather radio, or as complex as a satellite weather data system hooked up to a laptop computer.

All of the gadgets in the world don't equal experience, however. Some long-time succesful chasers go out with almost no gear, yet are able to consistently catch tornadoes using their years of skill and practice.

Can you make money chasing storms? Are there any storm chasing jobs?

SHORT ANSWER: No, it is not realistic to expect to make a career out of storm chasing.

LONG ANSWER: Unfortunately, there are no realistic career opportunities in storm chasing. The idea of a real "storm chasing job" is a myth. And by "career", I mean a job that not only covers your equipment and gas money, but allows you to pay a mortgage and buy groceries.

Hear me on this: if there were such things as careers for storm chasers, I would have one! Few people would love to have a full-time chasing job more than I would. Consider that I am better positioned in life than most to be able to have a storm chasing career - my day job is flexible, I have years of media experience and over two decades of experience as a chaser, and I have a strong love for weather and a motivation to be involved with it as much as I can. But, I've worked in web development as my primary career through all my years as a storm chaser.

My not having a storm chasing job is not for lack of trying. I have spent much of the past decade putting serious efforts toward finding creative ways to develop my storm chasing into a job that I can live on. So far, I have not been successful in this, and do not realistically ever expect to be. Many other longtime, dedicated and skilled chasers share my experiences - the opportunities are simply not there. If these "storm chasing jobs" did exist, we'd be the ones filling them!

Any careers from chasing are limited to a handful of the 'best of the best': those with many years of experience, near-endless capital expenditure ability/free time, and a penchant for pinpoint-accurate forecasts. 99% of chasers in the hobby are outside of that rare demographic. And even for those lucky and skilled few, the income potential is not as great as you might think. Storm chasing is first and foremost a hobby, and is rarely done professionally. Chasing is very expensive, and those that do bring in revenue at it usually only do so to recover some of their costs - very few actually make a profit.

All that said, there are five very difficult and limited ways that one can earn revenue by chasing storms. By revenue, I do not mean profit. As I said, profit (IE paying for both your chasing expenses and your cost of living) is not realistic, and hopefully after you read this, you'll see why:

- Video and Photography Sales:

Some chasers are able to sell video of tornadoes, lightning and hurricanes to news media, production companies and television shows. However, the amount received for video is usually not nearly enough to cover the cost of obtaining the footage. Storm footage is very difficult and expensive to gather, and there is a great amount of competition from media crews and other chasers. A chaser who sells video of a tornado has usually spent a week, or a month, or even years driving around the Plains, paying for gas and lodging out of his or her pocket all the way. He or she must beat out all other competition to get their video to media outlets first, which often means 'breaking off the chase' and leaving a good storm early to feed video. Most media outlets cannot afford nor are willing to pay enough for a chaser to recover all of their costs, let alone make a profit. Add to this fact that on any given storm in the Plains, there will be hordes of chasers filming the same thing you are. The laws of supply and demand also apply to weather video, and those types of situations end up saturating the market for video and further reducing footage prices.

Exceptional or rare footage, such as a house lifting up into the air in a tornado, can bring in a huge profit. But obtaining such a shot is a one-in-a-million occurance, one that will simply not happen to most chasers.

Ever since the rise of the smartphone, the rise of amateur video has further diluted the market for weather footage. Most people outside of the TV business do not realize that weather footage is valuable commodity to a television network, and normally commands a good price. But with today's proliferation of video cameras and video-capable cell phones, non-professionals are now more likely to capture weather events than the pro cameraperson. Not being aware of what their footage is worth, amateur photographers are willing to give their video away for free, enticed by the fleeting few seconds of having their name on TV. Most don't realize that this is like walking down to the upscale business park in town and handing your paycheck to one of the CEOs, as all of this free video is nothing more than a windfall for the networks. As this trend has continued, it has made it even harder for a storm chaser to break even with video sales to pay for gas and travel money, much less see any profit.

Aside from rare & exceptional captures, there is little or no market for generic still photographs of storms.

- Youtube & live streaming:

Online video publishing and live streaming has become another source of revenue for chasers. Like television licensing, this field is very competitive and earning any meaningful amount of mmoney from it is usually limited to the "best of the best" of chasers and photographers. These types of revenue streams are also very fickle: an algorithm change can make the views and revenue go away liteally overnight, even for the few chasers that do find some success.

- Local Television Coverage:

Some local television stations pay chasers (usually very little) to help cover severe weather affecting their viewing areas, but this is usually only done in regions where damaging weather is common (like the Great Plains or in hurricane-prone coastal areas). Even so, such chasers are not active unless severe weather is threatening - meaning they must have other income to survive during quiet weather and during the winter months. Chasing for a television station has its drawbacks, one of which is that the chaser is usually not free to go where the best storms are occuring. The TV chaser is usually stuck in the home viewing area if there is any chance that severe weather may affect it, which many times means lost opportunities for better storms and tornadoes farther away. With few exceptions, most TV stations do not pay chasers very well, if at all. It is common for only the chaser's gas money to be covered, and not much else.

- Storm Chasing Tours:

Another specialized business in the storm chasing world is that of chase 'tour' operators. These companies buy one or two 15-passenger vans and a good (very expensive) insurance policy, and take willing customers out to Tornado Alley to show them storms and tornadoes. Their clientele ranges from curiosity seekers to first-time chasers looking to learn more. The benefits of a chase tour are that the customer needs not be an expert at weather forecasting nor purchase their own equipment - they pay the tour operator for his expertise, transportation and lodging for a one-time 'adventure' in Tornado Alley.

A chase tour venture has many challenges, and is again realistically only an option for a chaser with many years of experience. First, the tour operator must be a seasoned and highly skilled chaser, one who is very competent at forecasting and can consistently find tornadoes, on his own, for his or her customers. A tour operator must be willing to accomodate and pander to the needs of 10 to 20 paying customers while safely carting them around the Plains. Finally, the tour operator must have other income to survive during the 10-month 'off season', and be able to find a day job that will allow for two months off every year.

- Science & Research Projects:

The fourth type of storm chasing 'job' involves being part of a sceintific team or research group, such as those sponsored by colleges, univiersities, government agencies and private corporations. These opportunities are usually very limited in scope and funding, and only a handful of people can expect to be employed by them. Once again, research chasers are only active during severe weather season, meaning they must have other income to make a living the rest of the year. For the very few that do manage to make a career from storm research, the actual chasing takes up a very small percentage of their time - the rest is spent in a lab analyzing data, maintaining equipment, etc.

In essence, anyone seeking to establish a career in storm chasing will find there are little or no realistic options available to them. If you chase, you chase as a hobby, with the occasional video sale here and there to help defray your travel expenses.

What is it like to chase storms?

It's great to get out and witness the spectacular displays in the skies. The drives are long sometimes, and the successful days are few. But the weather is fascinating, the camraderie enjoyable, and the experiences memorable - making it all worthwhile. You can get a glimpse of what storm chase expeditions in Tornado Alley are like by reading some storm chasing logs.

Interested in reading more? I will occasionally blog about storm chasing topics, addressing issues, myths, events, news items related to chasing. I have compiled most of these articles here.

GO: Home | Storm Chase Logs | Photography | Extreme Weather Library | Stock Footage | Blog

Featured Weather Library Article:

|

|