|

San Andreas Fault Tour: Parkfield to the Salton Sea, California

FULL GALLERY: All San Andreas Fault photos in gallery format

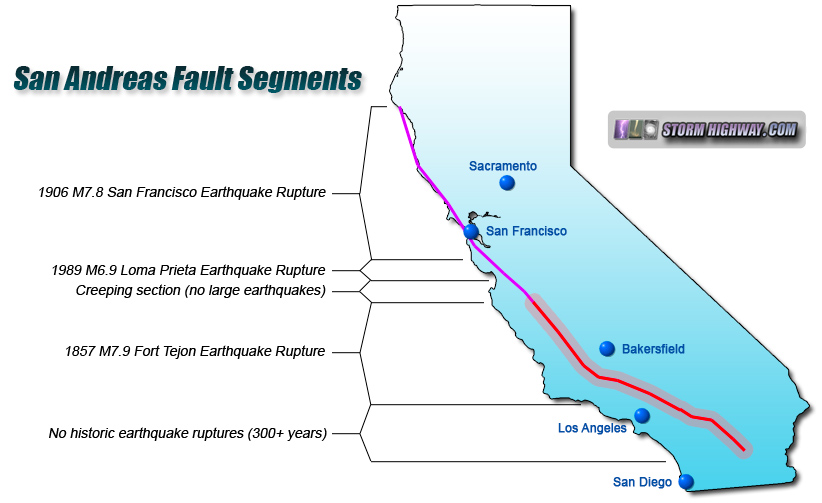

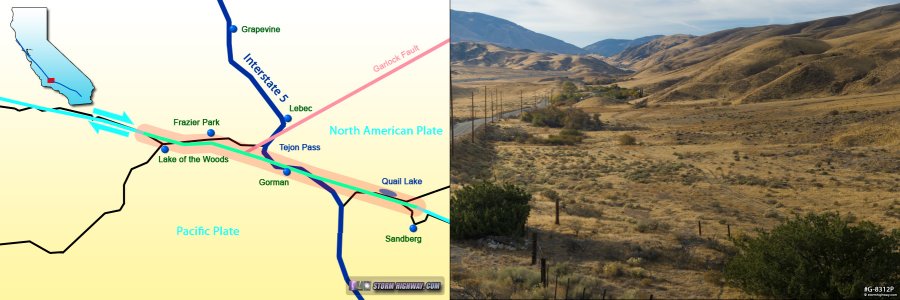

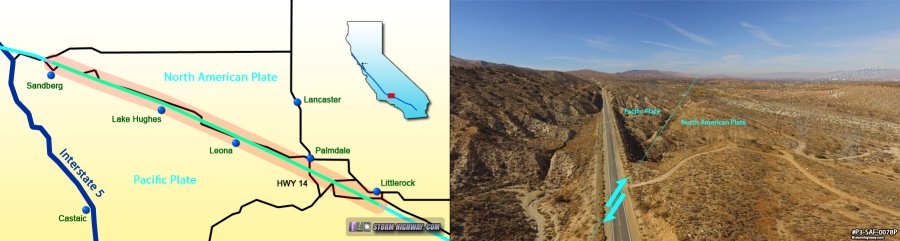

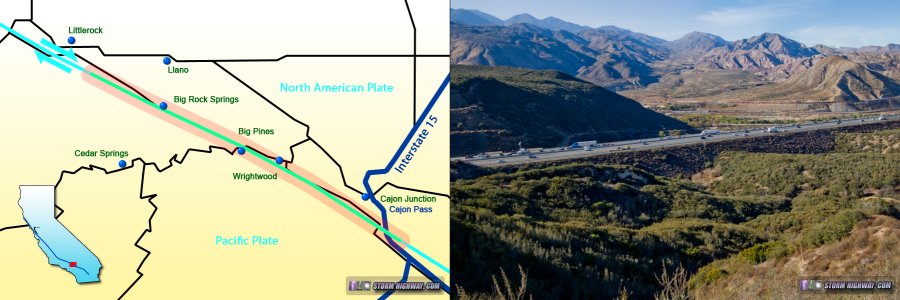

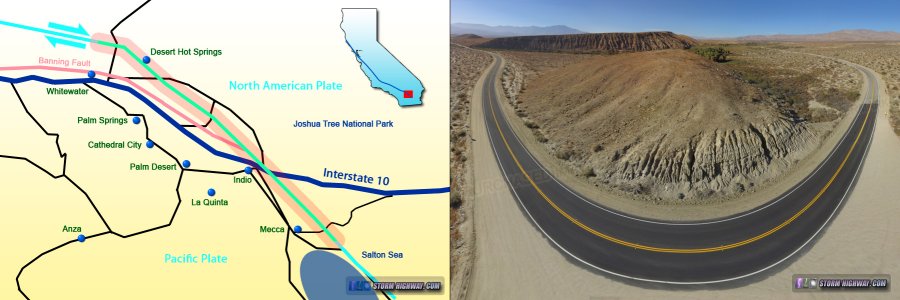

The southern San Andreas Fault from Parkfield to the Salton Sea in southern California is considered by seismologists as a prime threat for a major earthquake (exceeding magnitude 7) in the near future. The fault marks the boundary of two massive blocks of the earth's crust called tectonic plates: the Pacific plate to the west and the North American plate to the east. The Pacific plate moves north relative to the North American plate at a constant speed of 1.5 inches per year. In most places along the San Andreas, the two plates stay locked together for a hundred years or more - the elastic strain slowly and steadily building in the rock along the fault zone. Eventually, the accumulated tectonic strain overcomes the frictional strength of the rock, and the two sides slip suddenly and violently past each other in a matter of seconds: an earthquake.

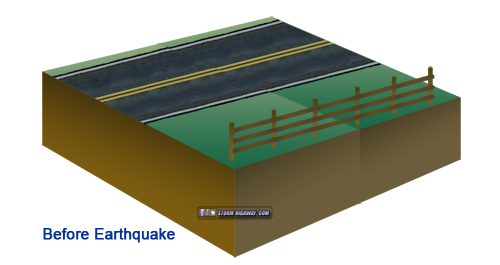

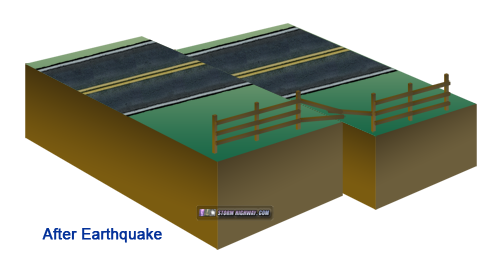

Illustration of the right-lateral strike-slip fault motion during earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault

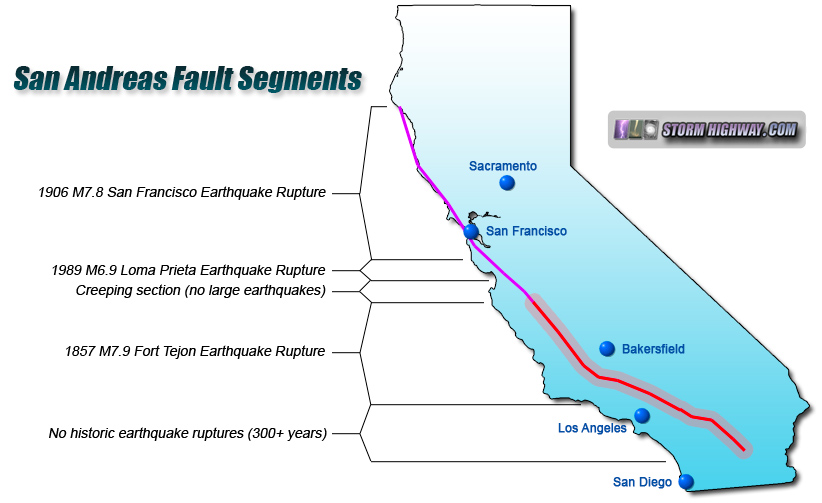

Science tells us some key facts about the southern San Andreas' threat. First, the two tectonic plates that create the fault zone are continuously moving relative to each other, slowly accumulating strain in the parts of the fault that are locked together. Second, trenching studies along the fault zone have revealed that the average recurrence interval for major earthquakes in these regions is on the order of 100 years. And finally, much of this "locked" section of the fault has not ruptured in more than 160 years - most recently in the magnitude 7.9 Fort Tejon earthquake of 1857. The far southern segments of the fault (which move slower, due to the plate motion being accommodated via multiple faults), have been dormant for much longer, over 300 years. It is inevitable: all of that accumulated strain has to be released at some point. It could be tomorrow, it could be in 30 years - but scientists agree it is certain to come.

|

The red highlighted section of the San Andreas Fault on this map is thought to be primed for a major earthquake. In this web feature, we will be touring this section.

RESOURCES: Learn more about earthquakes and seismology

This photo tour of the southern San Andreas Fault covers this "locked and loaded" segment, all or part of which may soon rupture in a major earthquake. If the entire 500-kilometer (310 miles) length of the fault shown in these images were to rupture, the resulting earthquake would exceed magnitude 8! Any earthquake generated by rupture on this section of the San Andreas will inflict high impacts on the Los Angeles metro area, thus, the fault zone has been an area of heightened monitoring and study in recent decades.

Let's begin our tour of the southern San Andreas Fault, starting at the small, rural town of Parkfield, California >

Jump to a section of the fault on the tour:

GALLERY: All San Andreas Fault photos in gallery format

About the Author: Dan Robinson has been a storm chaser, photographer and cameraman for 33 years. His career has involved traveling around the country covering the most extreme weather on the planet including tornadoes, hurricanes, lightning, floods and winter storms. Dan has been extensively published in newspapers, magazines, web articles and more, and has both supplied footage for and appeared in numerous television productions and newscasts. He has also been involved in the research community, providing material for published scientific journal papers on tornadoes and lightning. |

GO: Home | Storm Chase Logs | Photography | Extreme Weather Library | Stock Footage | Blog

Featured Weather Library Article:

|

|